China: Through the Looking Glass and Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections

China: Through the Looking Glass presented at the Metropolitan Art Museum (the Met) in New York, 2015 and Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections currently exhibiting at the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences (MAAS) both aim to present a view of Asia from the western perspective. Admittedly, both exhibitions do not attempt to present a complete picture of Asia but instead explore how Asia is perceived, particularly the mythological reputation created by western designers and collectors. It is important to consider the challenges curators face when curating traditional objects from other cultures. As Cuban curator Geraldo Mosquera suggests it is important for curators to consider how, in a global world, they become “discoverers or transcultural Czars.” By examining both exhibitions, it is important to explore how curators, when presenting non-western cultures on an international stage, do not ignore past negative discourses such as ‘Orientalism’. Instead, they should acknowledge these past conversations. They should not pretend to present Asia from an Asian perspective if it is not, but instead, create conversations between cultural objects. It is particularly difficult for this to occur when an Institution’s collections may be influenced by the preferences of its collectors and donators. However, both China: Through the Looking Glass and Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections are successful in presenting Asia with an acknowledgement to the western viewpoint. Neither exhibition aimed to create a dialogue directly representing China but rather to stimulate the mythological narrative that has been created in the western world.

China: Through The Looking Glass

China: Through The Looking Glass was a monumental exhibition that took place at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 2015. This blockbuster exhibition was a collaboration between The Costume Institute and the Department of Asian Art.[1] The exhibition curated by Andrew Bolton with the help of Maxwell K. Hearn aspired to view China from a different perspective, to open people’s minds to understand orientalism in a new light. Traditionally, orientalism has been viewed from a “negative connotation of western supremacy and segregation” which is fundamentally explored in Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism produced in 1978.[2] The exhibition China: Through The Looking Glass, instead of focusing on this negative sentiment, decisively chose to reinterpret the notions of orientalism in the west “as an appreciative cultural response.” The objective was not to look at the assimilation of culture by western fashion designers, but rather, to review how both western and Chinese designers have been inspired by Chinese cultural traditions.[3] Conversely Kevin Chua, art historian, suggests that ignoring uncomfortable issues and removing them from the exhibition could be“a shame.[4] This is because issues like orientalism have been at the centre of a debate for some time and therefore to simply ignore them does not resolve the issue. This then raises the question, what is Bolton’s role as Curator in framing Chinese culture and imagery outside of China to an audience that may not be familiar with eastern culture? His role is to educate the audience and stimulate conversations about the correlation of objects and art. Ihowever, it is also important for a curator to ensure nothing is omitted, ignored or changed simply to suit the institution. Bolton in an interview with the Washington Post notes “What I wanted to do was take another look at Orientalism...when you posit the East is authentic, and the West is unreal, there’s no dialogue to be had.”[5] Bolton’s strategies for this exhibition were to inspire dialogue and conversation. Bolton does not pretend that this exhibition is about the reality of China and its history and culture. Moreover, he ensures the audience understands that the exhibition is about the fantastical and mythological China that has been produced and reflected by the West. [6] By exhibiting traditional Chinese objects (from both the Met’s collection as well as iconic loans from The Palace Museum, Bejing] next to haute couture, the audience is able to both reflect on shared ideas and heritage, and also to consider “new creative possibilities”[7] between the cultures. The exhibition was set up to inspire dialogue and groups these conversations into two categories. It is important to consider whether the Chinese traditional objects are only being legimitsed by the presence of euro-centric interpretations? As further explored below it will become clear how curators reflect certain narratives and perspectives of Chinoiserie. In this case, China: Through the Looking Glass portrays the mythological narrative created and reflected by European designers.

From Emperor to Citizen

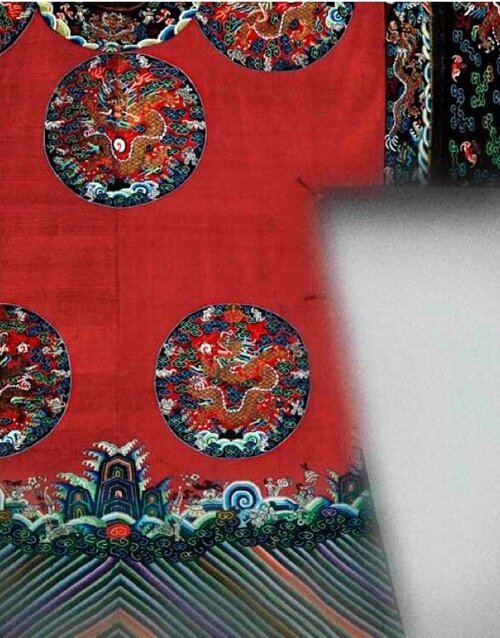

The foundational role of a curator as suggested by Terry Smith is to “make art public.”[8] This exhibition strongly indicates that the one fundamental aspect of a curator is to promote discourse and conversations between the audience and the objects on display.[9] China: Through the Looking Glass carefully establishes a dialogue between traditional Chinese objects in contrast to reflections of Chinese culture as illustrated by haute couture. The first dialogue, “From Emperor to Citizen,” was inspired by the autobiography of the last Emperor of China, Aisin-Gioro Pu Yi , which was published in 1964 and infamously adapted to film by Bernardo Bertolucci, thus having a significant influence on the western imagination of China.[10] The conversations explored through the objects and dress of the exhibition emanate from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Republic of China (1912-49) and the People's Republic of China.[11] Interestingly, Imperial China still largely remains as one of the most honoured and respected periods of “social progression” in the western imagination.[12] For example, the Manchu robe has been one aspect of Chinese tradition which has continued to inspire western fashion designers. Importantly, the modern reimaginings by European designers have been displayed alongside the historical and traditional Chinese dress. A fine exemplar is the Court robe from 19th century Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) which is crafted from China silk and metallic-thread tapestry (kesi) with painted details. Placed next to it is an evening dress by Tom Ford for Yves Saint Laurent. The dialogue created between the two objects could be interpreted as the European assimilation of Chinese culture. Instead the curators as translators, have facilitated an interaction between both objects in order for the audience to interpret the fashion statements by both designers. Thus the curator is translating a complicated history imbrued in the traditional objects into something like haute couture which they are most likely to be more familiar with. Bolton suggests that “designers typically gravitate toward the imperial dragon robe in all of it majestic splendour and richness. Clouds, ocean waves, mountain peaks, and in particular, dragons are presented as meditations on the spectacle of imperial authority.”[13] Thus, the curatorial invention of placing together two objects that although from different times and cultures have a common platform of fashion, enables an audience to engage in a positive way with cultures and times not of their own.[14] Thus, the museum and curators of the exhibition can influence an audience’s educative experience to reach beyond the museum and into everyday life.[15] The designers, inspired by the historical cultural objects are not aiming to claim ownership over the object, their intentions instead sit outside “rationalist cognition,”[16] which means that they are more interested in the aesthetic qualities rather than the “cultural contextualisation.”[17] Furthermore, Gabriel Lovatt warns that presenting only the mythological China “displaces the dynamism of a political state and its subjects—a process that powerfully shapes modernist ideas of China and the dissemination of those ideas.”[18] China: Through the Looking Glass delivered the right balance by not even pretending to represent the full richness of China’s history. The curatorial placement simply facilitated the audience to see inspired Chinese cultural objects next to the mythological imagining by the west. This means that China’s identity is not “engulfed”[19] and thus the curator becomes a translator of the concepts and source of inspiration. Ultimately therefore, this illustrates that curators are responsible to present and interpret certain narratives of history. This exhibition moreover aspired to present a new and different narrative of collaboration between the east and west.

Court robe (detail), 19th century Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China Silk and metallic-thread tapestry (kesi) with painted details. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ellen Peckham, 2011 (2011.433.2). Photography © Platon

Court robe (detail), 19th century Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China Silk and metallic-thread tapestry (kesi) with painted details. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ellen Peckham, 2011 (2011.433.2). Photography © Platon

Emperor of Signs

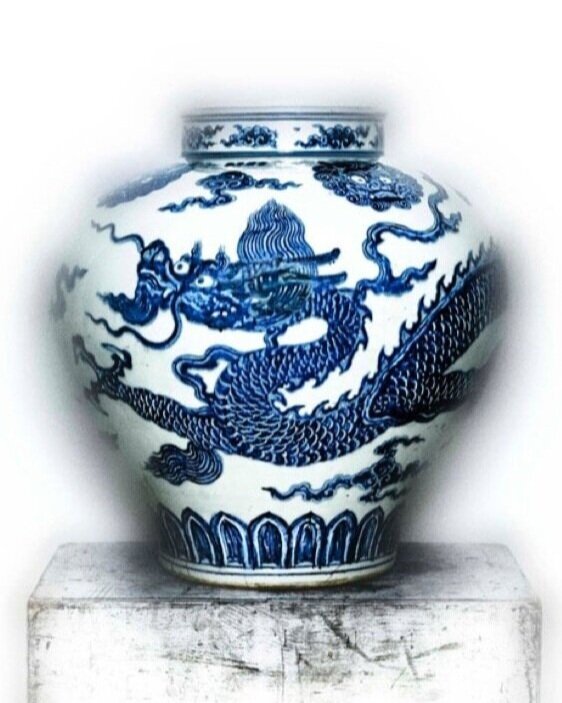

The next chapter of the exhibition “Empire of Signs” fascinatingly explores and sets up discourse between the cultural collaborations of the East and West. This section of the exhibition was inspired by Roland Barthes work Empires Des Signes (Empire of Signs), which are his reflections on Japanese culture after his visit to Japan. What is most interesting about this text is Barthes’ acceptance of simply observing significant aspects of Japanese culture rather than trying to understand them completely.[20] Similarly, China: Through the Looking Glass, explores how designers interpret and reflect on the aesthetical qualities of Chinese culture rather than understanding the political meaning. As outlined in the exhibition catalogue designers interpret the imagination of China with “free floating-signs.”[21] One fine example of this cultural collaboration between the east and west is Chinese Porcelain which was created in Jingezhen, China during the Yuan Dynasty period (1271-1368) and then exported to Europe.[22] The designs soon became popular and chinoiserie inspired porcelain began appearing on a larger scale in places such as the Netherlands, Germany and England.[23] Intelligently, the Chinese market adapted and pottery was created in China specifically for the European market. Bolton suggests that this object which is known as a Chinese cultural object is actually a “product of various cultural exchanges between East and West.”[24] One fine example of this is the dialogue created between a Chinese porcelain vase and a dress which features the iconic imagery of the blue and white porcelain patterns. By placing The Jar with Dragon, early 15th century Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) vase and the Roberto Cavalli evening dress, fall/winter 2005–6 the curator is intimating a positive cultural collaboration between east and west. The exhibition suggests that reproductions, like the Roberto Cavalli evening dress are not supposed to be understood as copied objects. Instead, the dialogue that is created by placing them together suggests that it is about cultural interaction of a contemporary global world.[25] However, could these objects be read as assimilating a culture for its own purpose? Curator Geraldo Mosquera suggests that “the world is practically divided between curating cultures and curated cultures.”[26] Therefore are designers, as “the curating culture” enabling the practice of re-appropriating cultures, to legitimise and allow for purchase in the western world? ”[27] When western cultures (such as Europe) adapt works of these curated cultures (such as China) they force the curated cultures to adapt their artistic practice. [28] This raises the question that of was this an important aspect of the Chinese Porcelain trade that was left out of the exhibition and instead called ‘cultural collaboration.’ It is important for cultural producers, such as China, to have control over the discourses surrounding cultural objects, such as porcelain.[29] Bolton disagrees and suggests that although these objects create a dialogue between one another, each item should be looked at and “appreciated” on their own first, before they are compared.[30] Thus, as one can see, Bolton with the help of Hearn aspired to present the imaginings of China in the western imagination rather than the reality. It is fascinating to see the presentation of objects of western origin next to objects and cultural materials which originate from outside of the western world.[31]

Roberto Cavalli (Italian, born 1940) Evening dress, fall/winter 2005–6 Courtesy of Roberto Cavalli. Photography © Platon

Jar with dragon, early 15th century Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Xuande mark and period (1426–35) China Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Robert E. Tod, 1937 (37.191.1) Photography © Platon

Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections

In contrast, Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections currently exhibiting at MAAS explores the historical Asian collection which has been developed over the last one hundred and forty years. The exhibition is curated and organised into themes of materials such as wood and lacquer, ceramics, metalwork, traditional dress and textiles, and contemporary art and fashion - themes which were overlooked by key Australian collectors of Asian art. The Powerhouse Museum suggests that this exhibition “gives insight into the many reflections of Asia, from a place of exotic curiosities to an active agent in contemporary culture.”[32] In a similar fashion to China: Through the Looking Glass, the exhibition does not claim to inform viewers of the exclusive narrative of Asia but instead offers “reflections.” Moreover, it aims to serve as an exploration of the “enduring western fascination with Asia”[33] Similarly, to China: Through the Looking Glass in New York, this Australian exhibition looks at the inspiration taken by the west of technologies and fashions which have inspired Australians. This exhibition is successful in presenting an exhibition that is exclusive to the Australian, and therefore, western perspective on Asia.”[34] Interestingly, the introduction wall text of the exhibition even mentions the “exotic”[35] imaginings of Asia. It is curious to note too, how the collectors featured, such as Gene Sherman (who has donated many Japanese items to the fashion collection at MAAS) and Judith Neilson influence the collection and therefore shape the way Australians view and interact with Asian art. [36]Gabriel Lovatt considers how “exoticism” stems from the way Europeans collect Asian art.[37] She suggests that Asia was once viewed as a producer of exotic objects rather than a country which undertook changes to commensurate with the West.”[38] Therefore it is important for the curators, when exhibiting Asian art, not to forget or ignore the negative connotations and sentiments such as orientalism. Instead, curators should acknowledge this past to create relative dialogues between objects.

Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections, The Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences

Traditional 1940’s Hong Kong Cheongsam (middle) was placed next a dress (right) of a similar fashion designed by John Galliano for Christian Dior in 1997.

Beatrice Grafton suggests that “If you’re afraid to get things wrong you never do anything, and what we’ll have is our museums and galleries being about nothing but dogma.”[39] Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections was highly successful because it presented the specifically Australian view of Asian art and the collections which we hold. It is important to note, therefore that when presenting collections of Asian art specifically in Australia curators must consider the audience in the Australian context. [40] This is because China has a large immigrant population in Australia and discourse surrounding identity and what it means to be Asian-Australian is becoming more prevalent.

Comparable to China: Through the Looking Glass, this Australian exhibition, placed modern objects inspired by Asian technologies next to the traditional cultural ones. One exemplar, was the Chinese Cheongsam. A traditional 1940’s Hong Kong Cheongsam was placed next a dress of a similar fashion designed by John Galliano for Christian Dior in 1997. Interestingly, these objects explore the dialogue or “cultural collaboration” that has occured between the east and west. The Cheongsam or Qipao overtime began to see influences of western tailoring. Conclusively, like the exhibition at The Met, Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections at the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences does not aim to tell the narrative of Asian art but instead reflections of it exclusively to Australia.

Cultural Collaborations

China: Through the Looking Glass and Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections are both successful in presenting Asia from the western viewpoint. Neither exhibition claimed to represent the historical happenings of Asia, each took the approach to deliver a historical mythological narrative that as created by western artists and fashion designers. These exhibitions make clear however that in a today’s global market positive cultural collaboration can occur and that as a society we can learn from each other’s cultural traditions.

References

[1] “China: Through the Looking Glass” The Metropolitan Museum, accessed 1 November, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2015/china-through-the-looking-glass

[2] Andrew Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces” in China: Through the Looking Glass edited by Andrew Bolton with John Galliano. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), 17.

[3] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,” 18.

[4] Kevin Chua, “Exhibiting Modern Asian Art in Southeast Art,” in Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 13, no. 2 (March/April 2014): 105.

[5] Robin Givhan, “The fantasy of China: Why the new Met exhibition is a big, beautiful lie, ” The Washington Post, May 5, 2015.

[6] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,” 20.

[7] Maxwell K. Hearn, “A Dialogue Between East and West” in China: Through the Looking Glass edited by Andrew Bolton with John Galliano. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015), 14.

[8] Terry Smith, “Mapping the Contexts of Contemporary Curating: The Visual Arts Exhibitionary Complex”, Journal of Curatorial Studies 6, no. 2 (October 2017): 170.

[9] Kate Fowle, “WHO CARES? Understanding the role of the curator day” in Cautionary tales: critical curating, edited by Steven Rand and Heather Kouris. (New York: apexart, 2007), 28.

[10] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces”, 20.

[11] Ibid., 18.

[12] Gabriel Lovatt, “Ming Vases, China dolls, and Mandarins: Examining the curation of China in the Galleries of Modernist little magazines, 1912-1930”, Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 37, no. 1 (2013): 129.

[13] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,”19.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Lovatt, “Ming Vases, China dolls, and Mandarins,”136.

[16] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,” 19.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Lovatt, “Ming Vases, China dolls, and Mandarins,”136.

[19] Michelle Antoinette, “Exhibiting Southeast Asian Difference: Global and Regional currents”, Cross/Cultures, vol. 178, no. 1 (2014): 160.

[20] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,”19.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid., 20.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Geraldo Mosquera, “Some Problems in Transcultural Curating,” in Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts, edited by Jean Fisher. (London: Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, 1994), 135.

[27] Mosquera, “Some Problems in Transcultural Curating,” 135.

[28] Ibid., 135.

[29] Olu Oguibe “A brief note on internationalism” in Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts, edited by Jean Fisher. (London: Kala Press in association with the Institute of International Visual Arts, 1994), 50.

[30] Bolton, “Toward an Aesthetic of Surfaces,” 20.

[31] Antoinette, “Exhibiting Southeast Asian Difference,” 176.

[32] “Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections,” Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, accessed November 1, 2018. https://maas.museum/event/reflections-of-asia-collectors-and-collections/

[33] Wall Text at Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections

[34] Okwui Enwezor, “The Politics of Spectacle: The Gwangju Biennale and the Asian Century”, Invisible Culture, no. 15 (2010): unpaginated.

[35] “Reflections of Asia: Collectors and Collections,” Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences

[36] Helena Reckitt, “Support Acts: Curating, Caring and Social Reproduction” Journal of Curatorial Studies 5, no. 1 (February 2016): 6.

[37] Lovatt, “Ming Vases, China dolls, and Mandarins,”126.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Beatrice Gralton, “Curating Chinese Contemporary Art in an Australian context”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, vol. 16, no. 2 (2016): 262.

[40] Gralton, “Curating Chinese Contemporary Art in an Australian context”, 253.

© Amelia Elsmore, 2022. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Amelia Elsmore and ameliaelsmore.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.