Chapter 3: Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination

“While the fashions that comprise this journey might seem fanciful, they should not be dismissed lightly, for they not only embody the imaginative tradition of Catholicism but also exemplify its propensities for storytelling.” — Andrew Bolton, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination

Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination opened on the 10th of May 2018 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute and swiftly became the most visited exhibition in the history of the institute.[1] The high number of visitors to the exhibition not only demonstrates the popularity of fashion exhibitions but also fashion’s ability to provide an extraordinary visual experience to audience members.[2] Fashion was used to recontextualise the permanent collection of the Met through curatorial interventions and the decision to display art objects and contemporary fashion designs together across the permanent collection of the Met, at the Cloisters and in the Fashion institute. The meeting of two artistic worlds provided a complete narrative of the catholic imagination.[3] The catholic imagination is the belief that, God, having created the universe, is present in everything that is created such as sacramental objects.[4] More than simply exploring the Catholic imagination, the exhibition sought to illustrate the immense influence that the catholic imagination has had and continues to have on contemporary designers (most of whom, in some way, had a personal experience of the Catholic tradition) by creating a series of conversations between contemporary fashion, ecclesiastical garments and medieval art from the Met’s permanent collection.[5]

To explain the catholic imagination, Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge of the Costume Institute, took Andrew Greely’s extended essay The Catholic Imagination as his inspiration. Greely defines the catholic imagination as being “the metaphorical nature of creation. . . . Everything in creation, from the exploding cosmos to the whirling, dancing, and utterly mysterious quantum particles, discloses something about God and, in so doing, brings God among us."[6] The catholic imagination is, then, the visualisation of the catholic culture which strengthens and inspired individuals’ faith. Without these visualisations, there would be no host for Catholics to connect with. The exhibition successfully portrayed an entire catholic aesthetic because of the weaving together of fashion, art and visual culture.

This chapter will explore what is generated when couture designs are integrated into the Met’s permanent collection to provide a “new evaluation” of the catholic narrative.[7] It will argue how the careful curatorial decisions to place fashion with art objects equates to a complex form of ‘storytelling’, that the audience leaves with a complete understanding of the catholic narrative as a whole material world is brought together.[8] This visual imagery becomes more significant because the audience is able to compare differing interpretations of catholic imagery to understand how it functions to narrate specific stories. For this exhibition doesn’t simply just display fashion, it also re-contextualises the space of the Met’s permanent collections to demonstrate how both art and fashion are aesthetic creations which are judged depending on the space that they occupy whether that be social or economic.[9] The conversations that result in the story telling of the catholic imagination can only occur when an audience is launched into an entire aesthetic which is brought together by art, fashion and material culture.

By placing these garments amongst traditional museum objects and re-imagining the space to communicate the narratives of the catholic imagination, the garments have the role of widening access to the narrative and medieval objects. The exhibition begins with garments which use overt Christian symbolism such as crosses or specific designs worn by religious orders. It seems that this specific curatorial decision means that the audience is able to connect the ideas because some garments have been placed next to the object that directly inspired them. Once the audience has the fundamental knowledge of these overt applications, they are then able to move onto more conceptual reflections on the catholic narrative which may not be as clear.[10] By positioning the museum objects next to these more conceptual works, the viewer is encouraged to engage with the symbolism present in the exhibited works. The audience connects these conceptual ideas to the literal and the narrative is completed. This communicates how contemporary fashion designers use storytelling, narratives and metaphors to communicate to their audiences a specific meaning.[11] In a very similar process, the museum objects which are created out of the catholic imagination, use storytelling to communicate the sacramental values of the Catholic Church. It creates a visual manifestation of religious ideas, which is exactly what these fashion garments achieve.

By the time the audience have been thoroughly introduced to the catholic narrative they are faced with the Vatican collection from the Sistine Chapel. The Costume Institute partnered with the Vatican to bring ecclesiastical garments, such as Copes and Papal Tiara’s to the museum that acted as a “cornerstone” to the exhibition.[12] Placed on their own in the Anna Wintour Costume Centre audiences were able to acquire a close look at the high level of detail in the works. Once the audience has moved through the space, they begin to appreciate the conversation between contemporary fashion design and religious objects. This is because it demonstrates the extremely creative designs which explore outside the boundaries of the Catholic church.[13] By displaying contemporary fashion designs amongst the Met’s permanent collection it results in a highly successful story-telling of the catholic narrative because the audience are launched into a matrix of the catholic imagination.

The re-purposing of The Met’s collection combined with the placement of new cultural objects into the space means that a new narrative can be created. It furthers the meaning of the objects and allows them to be compared with contemporary perspectives.[14] Visitors that may frequent the permanent collection will be presently surprised to see how items share qualities with contemporary fashion design. It stresses the importance of fashion as an adaption of culture to gain a deeper understanding of both the art object and garment beyond its aesthetic experience. It is clear that the Costume Institute does not aim to appropriate couture into the category of fine art but instead display it as its own entity to illustrate the “artistic merit” of couture.[15] Bolton finds the comparison between fashion and art to be “reductive” and “frustrating.”[16] Bolton does make a point for the fact that although fashion and art share similar creative qualities they should not be put against one another because they are differing interpretations on culture. The discourse created from their interactions illustrates that it is the curatorial placement which contextualises an object. In other words, contemporary haute couture displayed in a museum space will take on different meaning to when it is presented on a runway. The costume Institute’s unique structure – purely focused on fashion – means that it is able to push boundaries with the display of dress because their sole purpose is to collect and display fashionable dress. [17]

The exhibition was not, as Bolton explains, designed to simply narrate the components of the catholic imagination such as the objects, events and persons that allude to the presence of God.[18] Instead, the contemporary fashion designs exemplify the designers tendencies for narrating beyond the catholic imagination of the church.[19] It is important to note the difference between the ‘catholic imagination’ and the ‘catholic imagination of designers.’ As demonstrated in the first half of the exhibition, the catholic narrative has a long history and certain values to adhere to. This means that it is not fabricated. In contrast, the ‘catholic imagination of designers’ explores the narrative beyond the boundaries of the church. Resulting in the designer’s ability to communicate fabricated narratives, transporting the viewer into this fantasy world.[20] This reflection of the catholic imagination by both art forms is also forced onto the viewer through the experiential layout of the exhibition which takes the viewer on a pilgrimage. [21] The beginning of the pilgrimage is displayed at the Costume Institute which explores the Vatican’s collection and the influence of religious art on designers. To conclude the pilgrimage, one has to take a journey north across Manhattan to the Met’s Cloisters, where garments explore the worlds of religion and it appears that this was the most successful enclave of the exhibition because it created a fabricated world, allowing the visitor to forget that they are in a museum space.[22] The scenography translated the catholic narrative by providing “different dimensions” for which the story to be communicated.[23]

Like the Dior exhibition the use of the display space has been utilised to ensure the audience gains a profound understanding of each object because they experience it as a whole. This is seen through elements such as the surrounding architecture of the cloisters which presents itself as a monastery. Other material elements such as tapestries further add to this atmosphere because the audience are not just looking at objects in display cases but are surrounded by religious culture in all forms. The move away from traditional display of garments meant the audience is able experience the garment rather than just looking at a beautiful dress. Bringing fashion and art together adds another dimension to the curatorial vision of Bolton for the catholic imagination.

The Met’s cloisters present a majestic setting, which locate the garments within the gothic spaces to remind the audience of the catholic narratives that designers have been drawn to. The exhibition design cleverly brings together the two worlds of art and fashion in a subtle way because the garments become a part of that space. By placing garments in a non-traditional museum space, the narrative and stories behind the garments and objects become more convincing because you are not reminded of a museum setting.[24] The scenography transports weight of the curatorial argument which illustrates how the catholic imagination has had a huge impact on wider visual culture. [25] The fabricated environment underlines and immerses the viewer in a fantasy world transporting them into the Catholic Imagination of the designers.[26] For example, the Romanesque architecture displayed next to garments create an enhanced visual experience for the viewer because it brings both worlds together.

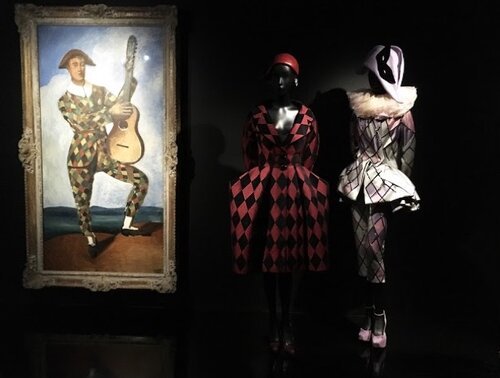

The visual impact of these two worlds is exemplified by an example of two evening ensembles by Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli for Valentino, displayed in the Saint-Guilhem Cloister. [27] The interaction between the ensembles and Romanesque architecture is significant because it alludes to the rich history of Roman architecture and Valentino’s rich history based in the historical city.[28] This specific cloister houses elements from the Benedictine monastery in the village of Saint-Guilhem-le-Desért. The space evokes a sense of Romanesque style which the area is known for.[29] It is clear then that the Valentino evening ensembles were specifically selected to be displayed in this space as they both consist of references to Roman secular and religious architecture. [30] The complex idea’s (such as their reference to the significant religious history of Rome) which are present in these two garments are accentuated by the curators choice to utilise the compositional fictitious space which the viewer encounters.[31] This specific curatorial choice of a fabricated space meant that conversations are had between the garments and the architecture to explain a historical time which is experienced by the audience. [32] Jeff Weinstein explains “Like all art, clothing acknowledges history, yet at its most ambitious tries to supersede it.”[33] In this specific case, the placement of the Valentino garments acknowledges the important history that Roman architecture has played in fashioning the catholic imagination.

Both garments were from Valentino's autumn/winter 2015–16 haute couture collection which paid tribute to Rome as a city (see figure 3.1).[34] Rome has a strong history with the catholic tradition because it is the established residence of the pope and thus the pinnacle of the catholic faith. The experience created by the curator’s intervention is an imagining of Valentino’s encounter with the Romanesque architecture. [35] Both dresses were propped up high on thin pedestals in the middle of the space and sat diagonally across from one another. Natural light shone down upon the garments which is quite unusual as the audience are not used to seeing delicate garments under such direct light. [1] This puts the garment into direct conversation with the architecture which surrounds it. The audience begins to understand the designers encounter with important secular architecture. The garment has an added layer of meaning because it is connected to the histories of the space. The result of this curatorial placement means that the space produces new knowledge which it did not have before.[2]

If you would like to read more of this chapter please contact me.

[1] Leo O’Donovan, “The Fashion of Faith: ‘Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” National Catholic Reporter 54, no. 18 (2018): 15.

[2] Vänskä and Clark, “Introduction,” In Fashion Curating, 2.

[1] Harold Koda and Jessica Glasscock, “The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Evolving History.” In Fashion and Museums, 44; Julia Petrov, “The New Look: Contemporary Trends in Fashion Exhibitions” In Fashion, History, Museums: Inventing the Display of Dress (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019), 186.

[2] Oakley Smith and Kubler “Eye Candy and Ideas,” 154.

[3] Oakley Smith and Kubler “Art Meets Fashion,” 96.

[4] Andrew Greeley, The Catholic Imagination (Berkeley, Calif: University of California, 2000), 9.

[5] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 96; “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.” Metropolitan Museum of Art accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/heavenly-bodies.

[6] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 96; Greeley, The Catholic Imagination, 11-12.

[7] Petrov, “Introduction: Fashion as Museum Object,” 10.

[8] Petrov, “The New Look,” 195.

[9] Steele “Fashion,” In Fashion and Art, 13; Petrov, “The New Look,” 186.

[10] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 95; Hazel Clark, “Conceptual Fashion,” In Fashion and Art, 74.

[11] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 95.

[12] “Versace and The Met’s Costume Institute Spring 2018 Exhibition – Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and The Catholic Imagination.” Versace. Accessed April 3, 2019. https://www.versace.com/international/en/world-of-versace/stories/versace-at-the-met/

[13] William Keenan, “From Friars to Fornicators” In Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination, 399; Vänskä, “Boutique – Where Art and Fashion Meet,” In Fashion Curating, 131.

[14] Melchior, “Introduction,” 29.

[15] Gwyneth Williams, “Exhibition Review – Masterworks: Unpacking Fashion” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 5, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 125.

[16] Williams, “Exhibition Review,” 125.

[17] Sarah Scaturro and Joyce Fung, “A Delicate Balance: Ethics and Aesthetics at The Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,” in Refashioning and Redress: Conserving and Displaying Dress, edited by Dinah Eastop and Mary Brooks (Getty Publications, 2017), 160-162; Vänskä, “Boutique – Where Art and Fashion Meet,” In Fashion Curating, 131.

[18] Greeley, The Catholic Imagination, 10.

[19] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 95.

[20] Eleanor Heartney, “The Met’s ‘Heavenly Bodies’ Show Mines Catholicism for Eye Candy, and the Result Is Both Gorgeous and Unsettling.” Artnet News, May 10, 2018; Frederick Roden, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination (2018).” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking 5, no. 3 (2018): 213.

[21] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 96.

[22] McClendon, “Review of ‘Heavenly Bodies.”; Roden, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York, Heavenly Bodies,” 205; Jason Farago, “Jason Farago, “A Trinity of Opinions on the Met’s ‘Heavenly Bodies,’” The New York Times, May 20, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/20/arts/design/met-museum-heavenly-bodies-catholic-imagination.html; Lidija Haas, “Shock and Awe: Haute Couture Proves No Match for Some Lavish Loans from the Vatican,” Apollo, September 2018, Vol 188, Issue 667 edition.

[23] Petrov, “The New Look,” 195.

[24] Oakley Smith and Kubler, “Eye Candy and Ideas,” 155.

[25] Petrov, “The New Look,” 195.

[26] Heartney, “The Met’s ‘Heavenly Bodies’ Show.”; Roden, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York, Heavenly Bodies,” 213.

[27] “Exhibition Galleries: The Met Cloisters,” The Met, accessed April 18, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/heavenly-bodies/exhibition-galleries-met-cloisters

[28] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 220.

[29] “Exhibition Galleries: The Met Cloisters,” The Met.

[30] Petrov, “The New Look,” 193-4.

[31] Crawley and Barbieri, “Dress, Time and Space,” 69.

[32] Crawley and Barbieri, “Dress, Time and Space,” 73; Judith Clark, “Props and Other Attributes: Fashion and Exhibition-Making,” In Fashion Curating, 96.

[33] Weinstein, “Is Clothing Art,” 72.

[34] Bolton, Heavenly Bodies, 220.

[35] Crawley and Barbieri, “Dress, Time and Space,” 76.

© Amelia Elsmore, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Amelia Elsmore and ameliaelsmore.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.